AUGUSTA — Lawmakers heard hours of passionate testimony Monday about obscenity, literature and censorship as they considered a proposal to require teachers to notify parents or students before utilizing sexually explicit materials in classrooms.

Bill sponsor Rep. Amy Bradstreet Arata, R-New Gloucester, and her supporters said parents as well as students should have the opportunity to opt out of reading or viewing “obscene materials.” Yet opponents pointed out that parents can already formally challenge a book’s usage with the local school board and compared Arata’s bill to previous attempts to ban works now considered classics of literature.

“Who is going to decide what is obscene? Who is going to police this law in all of our schools across this state?” asked Cathy Potter, a librarian in Falmouth’s public schools. “And are you prepared to prosecute librarians and teachers for putting books in the hands of our students … because this would make it a crime.”

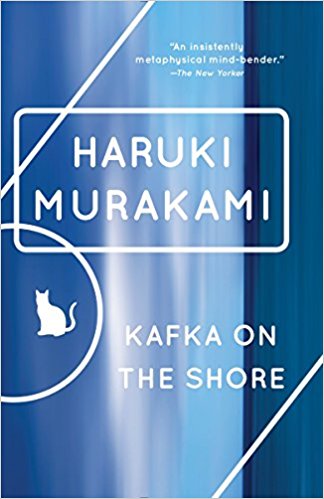

As an example of “the pornographic nature of materials being assigned to students in Maine,” Arata distributed excerpts from “Kafka on the Shore,” which was assigned to her son in the 12th grade. The 2002 book by Japanese author Haruki Murakami has won critical acclaim – including landing on The New York Times’ Top 10 list for 2005 – but contains some explicit descriptions of sexual activity as well as rape.

As originally written, Arata’s bill proposed that public schools be removed from the list of institutions – such as libraries or museums – that are exempt from the law prohibiting the dissemination of obscene materials to minors. That proposal garnered vociferous pushback from educators and others who recalled the moral policing that once led schools or entire states to ban literary classics such as “To Kill a Mockingbird,” “Of Mice and Men” and “The Catcher in the Rye.”

In response, Arata amended her bill to instead require teachers to provide written notice that the book or other materials contained obscene content or depictions of sexual assault. Both the students and their parents/legal guardians would need to provide written consent prior to receiving the materials.

“This common-sense bipartisan bill will give minors and parents the respect and dignity of choosing what is appropriate for them and their family so that they do not have to feel embarrassed, harassed or traumatized,” Arata said. She said the bill “will help make sure that all Maine schools are safe and nurturing environments for our children.”

Supporters the Christian Civic League of Maine, pastors and parents, as well as several survivors of sexual assault warned that graphic depictions or descriptions could further traumatize children who are victims themselves. Others objected to teachers’ selection of certain movies with objectionable material in their classroom curriculum.

Jennifer White of Gray said her then 11-year-old daughter was confused after watching a film in class that included both sexual content and depictions of a man committing suicide with a gun.

“Showing a movie with that type of graphic content and sexually explicit material can cause harm to a child that is not mature enough to handle it, and fifth grade is not mature enough to handle that,” White said. “This is one example of how L.D. 94 can better provide transparency to both children and families.”

But teachers, librarians and associations representing Maine’s school boards and superintendents urged lawmakers to reject a bill that would make it a criminal offense for teachers to teach literary texts that some perceive as obscene.

“The problem is that what is obscene to one person or group may be judged to have artistic or social merit to another,” said Claudette Brassil, a retired English teacher representing the Maine Council for English Language Arts. “Criminalization of literary choices is a detriment to academic freedom. As in the past, contemporary community standards continue to evolve and are influenced by many forces.”

Brassil, a Brunswick resident who taught at Mt. Ararat High School in Topsham, testified that literary works can sometimes provide a platform for students to talk about violence or sexual situations with adults. She also said that she believes children are becoming more willing to speak up to trusted individuals – including teachers – when they are victims of abuse.

Opponents also said the bill was unnecessary because school boards in Maine already have a process through which members of the public can challenge the suitability of educational materials and request a formal review. In fact, Arata used that process to successfully challenge the use of “Kafka on the Shore” in her children’s schools.

“This is a decision that I believe is best handled locally with your school board – people who you elect and most likely represent, as a group, the norms in your community,” said Victoria Wallack, representing both the Maine School Boards Association and the Maine Schools Superintendents Association. “That is where I would go first. I wouldn’t be here at the Legislature trying to change educational policy that is rightfully adopted … by the school board.”

The Criminal Justice and Public Safety Committee is expected to hold a work session on L.D. 94 next Monday.

Kevin Miller can be contacted at 791-6312 or at:

Twitter: KevinMillerPPH

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story