LEWISTON — July 2020 was a particularly dark and stressful time for the people who worked at the former Jones & Vining plant on Webster Road.

Not only was the reality of the COVID-19 pandemic rapidly unfolding around the world, but the very future of the company locally was simultaneously unraveling. The owners wanted out and announced they would be closing the building’s doors after 41 years, citing the pandemic as the primary reason.

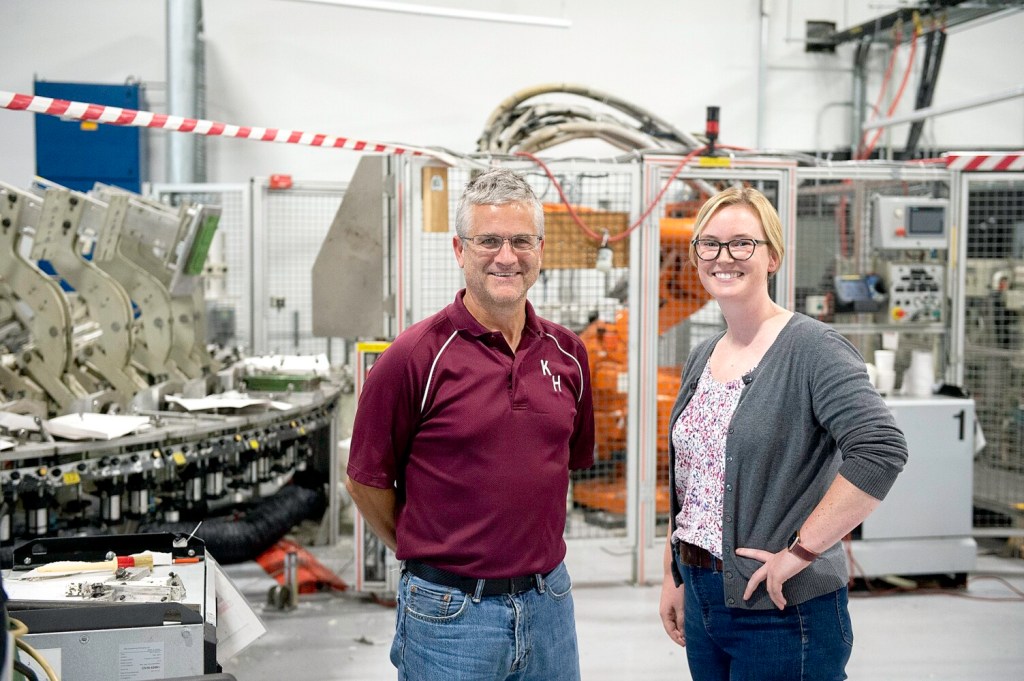

Purchase orders would carry the skeleton workforce of less than 25 through mid-September, with the weight falling on the shoulders of Managers Sarah Morrison and Dan Keeley to deal with customers and employees and ultimately close the plant down. Customers were in panic mode, but had nowhere to turn, especially as businesses were shutting down because of COVID-19.

“The employee base is starting to prepare for a separation, and you know some having 40-plus years of experience in the building,” Morrison said, “planning for that separation while continuing to have conversations with customers about what we can do and who can contribute and other people stepping in and saying maybe we should think about buying this.”

That’s exactly what happened. The “other people” included the Bose Corp. and other key customers who brought their influence to the table. The city’s economic and community development director, Lincoln Jeffers, helped bring together the Finance Authority of Maine and an investment group led by Portland-based Anania & Associates. All of them saw opportunity and after some discussions and negotiation, they reached and agreement with owners Jones & Vining in a deal reported as a $5.5 million acquisition.

A new company was born — Polymer Laboratories & Solutions, doing business as Poly Labs, and it meant no layoffs and no closure. Now what?

The first priority for Morrison, who was named chief executive officer, was to get Dan Keeley back. The former sales manager had accepted his severance and was running the ice rink at Kents Hill School. Keeley is now vice president of business development at Poly Labs.

Keeley stayed in touch with his customers, who breathed a collective sigh of relief upon hearing the news of the acquisition. “It’s not something you can just pick up and move somewhere else,” Keeley said. “It’s pretty complicated and there aren’t a whole lot of people in the country who do what we do, so it’s not like I’ll just move it to company B. We were fortunate that they all wanted to come back quickly.”

Jim Lavallee of Lisbon pours material into an insole mold July 13 at Poly Labs in Lewiston. Lavallee started working for the business 38 years ago when the name of the company was Jones & Vining.& Vining. Daryn Slover/Sun Journal

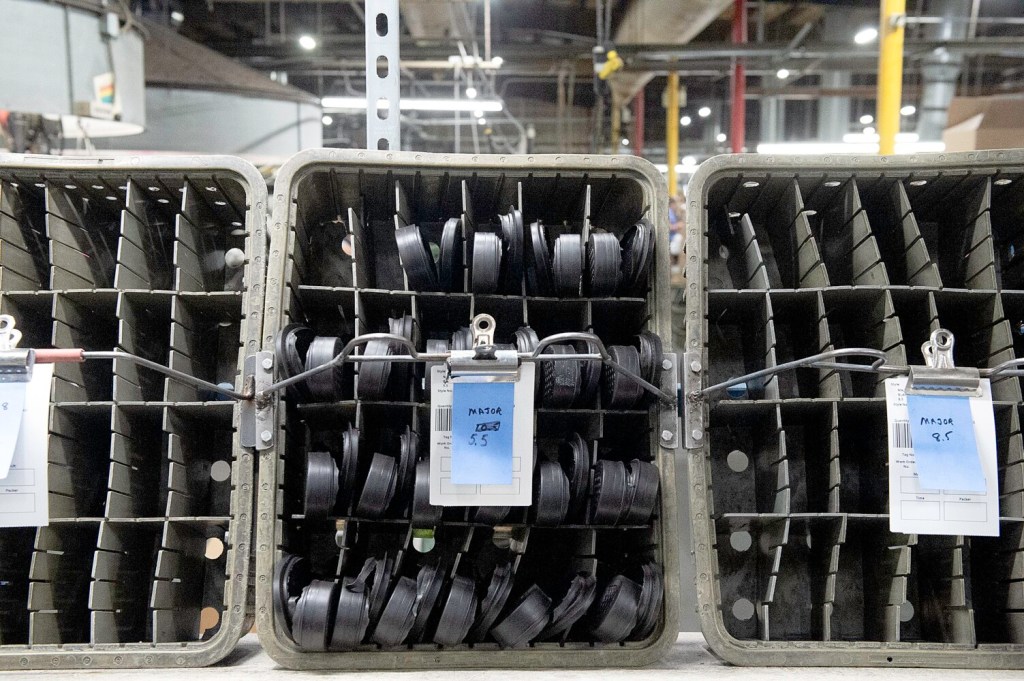

What they do at Poly Labs is pour and produce polyurethane foam products that many wear and use on a daily basis. They make insoles and outsoles for footwear — including the black dress shoes worn by U.S. Army officers. Outsoles are the piece of hard material on the bottom of the shoe.

They make helmet padding for Riddell that’s used in football helmets worn by high school athletes and the NFL, recoil pads for Remington rifles, medical positioning pads, air cushions for military headsets and the list goes on.

November and December remained hectic, especially for Morrison as they looked ahead to restarting the company anew, exchanging many phone calls and emails with clients to secure purchase orders, then getting pricing commitments and trying to source materials to make their products — a tall order for a fledgling company in the middle of a pandemic.

The company reached another milestone in February when it was able to advertise it was hiring. But amid the scramble to source materials, Texas was slammed with a winter storm that brought record cold, ice and snow to a state unaccustomed to dealing with a sustained winter storm. Millions were left without power and the petrochemical industry was crippled for months.

“Everything froze in Texas, that’s when we found out we buy materials from two major companies — BASF and Huntsman,” recounted Keeley. “But what we didn’t know was that all the raw materials they sourced to make our stuff in Michigan was all sourced from that Louisiana, Texas area.”

In August, Hurricane Ida came ashore in Louisiana as a Category 4 storm, further affecting the supply chain and availability of the chemicals used to make polyurethane products.

Morrison explained that because Poly Labs was “born” in November 2020, it had no historical purchase data and hadn’t even had time to set up contracts with suppliers.

“So, we had a big ramp-up and then we started having to regulate the schedule to the best of our ability,” she said. “Luckily we have a great team here and a very accommodating production crew that is transferable from job to job and had a willingness to say, OK here’s the material we have this week, this is what we’re running. We’ll shut this machine down and start something else up.”

Morrison said it was a painful time, but a learning experience for everyone at the plant.

Polyurethane foam pads inside a military helmet are made for Bose at Poly Labs in Lewiston. Daryn Slover/Sun Journal

Despite all the adversity and hurdles, Poly Labs is making inroads and is growing, less than two years into its existence. The company has 70 employees and is in the process of hiring up to 10 more in the next few months.

“We’re in the stages now where we are utilizing equipment, looking for better utilization of equipment, expanding to additional shifts,” Morrison said. They are also looking at expanding their footprint in the next few years, into a larger building. The 88,000-square-foot facility was built for the machinery that’s there and doesn’t leave a lot of extra room.

Poly Labs is investing in its research and development, and quality control lab and has hired two chemical engineers and a mechanical engineer to bolster the scientific bench. New robotic production machinery has been brought in to help streamline and increase production.

Other significant accomplishments include obtaining ISO 9001:2015 certification — an international standard of quality management and assurance — and acquiring the production rights and intellectual property license from polyurethane ear cushions used in military headsets from the Bose Corp.

It’s a lot of progress for a 40-year startup, as Morrison likes to call Poly Labs. But are the investors happy?

“They are happy,” she said, cracking a smile. “We are on track for our expectations for year two. We are meeting the expectations (revenue) and working through it at this point. Everybody is happy.”

“We’re just trying to approach things way smarter,” Kelley added. “Jones & Vining didn’t really care about big improvements. Now it’s like we’re trying to improve every day.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story