Experts in caring for intellectually disabled adults in Maine say there’s ample blame to go around in the case of a 62-year-old Biddeford man who died after he failed to receive insulin required to treat his diabetes.

After Norman Fisher’s death in late August, the Department of Health and Human Services took the rare step of canceling its contracts with the private company that operated the transitional home in Portland where he died. The provider, Residential and Community Support Services, has appealed that decision and said it’s being scapegoated.

Other treatment providers said even though DHHS likely did the right thing in taking decisive action against RCSS, the state still bears some responsibility, as Fisher was under the guardianship of a DHHS employee. They also point to the state’s record of lapses in meeting the needs of adults with intellectual disabilities, as well as a history of failing to thoroughly investigate deaths and serious injuries among this population.

Richard Estabrook, who until 2012 was chief of the now-defunct Office of Advocacy within DHHS, used to advocate for people like Fisher. He said he believes the state, as guardian, did have a responsibility to ensure that Fisher was placed in a safe, secure environment. But he also said staff at RCSS had a duty to provide him with emergency medical care.

Ray Nagel, executive director of the Brunswick-based provider Independence Association, said Fisher’s death was a failure of the system.

“The state is just as guilty as the provider, in part because it has failed to recognize the needs of those with significant behavioral challenges,” Nagel said, adding that he thinks the state did the right thing in cutting ties with RCSS and said the current administration seems to be trying to fix things. “DHHS can’t be blamed for the sins of the people before them. This is a long-neglected system.”

Fisher is the latest tragic reminder that even though Maine has spent three decades building a community-based system for caring for intellectually and developmentally disabled adults, significant gaps remain. Yet despite the fact that he had been in the state system for most of his life, and was under state guardianship since 2015, RCSS is being blamed for his death even though he was in their care just 72 hours.

Neal Meltzer, executor director of Waban Projects Inc., a Sanford-based service provider that provided case management services to Fisher but not in-home or medical care, said the man’s death is emblematic of a system that has been broken for a long time.

“This really rocks all of the providers and the people who knew him, and it causes us to do a deep reflection into our safeguards,” he said.

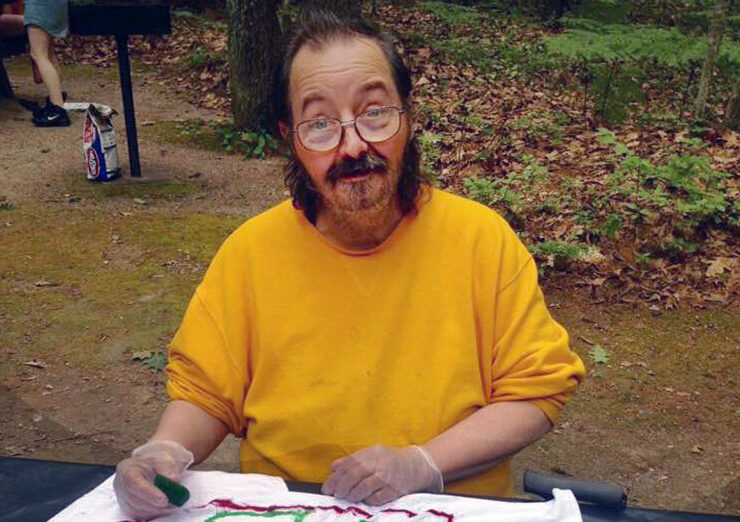

Art by Norman Fisher Photo courtesy of the Art Certificate Program of Biddeford

Maine DHHS spokeswoman Jackie Farwell said the state is confident in its decision to cut ties with RCSS and that many providers and members of the public have voiced support since that decision was made. She also said the state, under Gov. Janet Mills, has taken steps to improve care for more than 5,500 adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities who receive state and federal services, including implementing a better system for tracking reportable events, which include allegations of abuse or neglect. That change was spurred by a federal audit released in 2017 that documented numerous deficiencies.

More recently, DHHS has instituted a requirement that one- and two-bedroom homes for adults with disabilities – like the one in Portland where Fisher died – be licensed.

AGENCY BLAMES DHHS

Fisher died Aug. 27 at a two-bedroom house on Humboldt Street in Portland that was managed by RCSS, one of 38 such homes scattered throughout southern Maine. He shared the home with another client and they each received care.

Following his death, the state halted new admissions to RCSS, launched an audit and then decided a month and a half later to terminate its contract. The state now is in the process of moving 65 other RCSS clients.

Christine Tiernan, CEO of RCSS, said her agency was blindsided by the cancellation decision and the state, as Fisher’s guardian, was responsible for placing Fisher with her agency without his medication and for not intervening when he refused care.

“As Mr. Fisher’s legal guardian, DHHS’s unacceptable failure to provide essential information, life-saving medication, and adequate communication and support during the transition to the RCSS facility had devastating consequences,” the provider said in a statement.

RCSS employees are planning to protest the state’s decision at noon Monday outside DHHS’ South Portland office.

Farwell would not answer specific questions, or counter specific claims made by Tiernan, saying that was prohibited by patient privacy laws.

“We take seriously our legal obligation to protect the privacy of those who receive services from the department, which continue even after an individual’s death,” she said.

As a result, there are many unanswered questions, including, for example, whether Fisher’s guardian – Patrick Bourque, a DHHS employee – was involved in placing Fisher at the Portland residence managed by RCSS or whether Bourque was responsible for ensuring that Fisher had his insulin. Probate records indicate that Fisher was severely diabetic and sometimes needed assistance taking his medication.

The state has only said that RCSS “failed to administer critical medication and failed to summon emergency medical services when the individual experienced a medical emergency while in RCSS’ care.”

Portland police are investigating the circumstances of Fisher’s death. That investigation is ongoing, Lt. Robert Martin said last week, but he would not provide details. DHHS has been asked to hold off on its own internal investigation pending the outcome.

Lydia Dawson, director of the Maine Association of Community Service Providers, of which RCSS was not a member, said more can be done, including finding ways to pay direct-care workers more.

Additionally, she said, “An independent mortality review panel tasked solely with monitoring deaths and serious injuries cannot wait. Decisive and immediate action is needed to prevent future tragedies.”

Currently, death and serious injuries investigations are handled through Adult Protective Services, and law enforcement when appropriate.

Rep. Patricia Hymanson of York, a physician and House chairwoman of the Legislature’s Health and Human Services Committee, said she was impressed by the state’s decisive action against RCSS. But Hymanson also said she fears others might be at risk, not necessarily because of neglect or ill intent by any providers but because the system is under tremendous strain, which has only worsened with the state’s ongoing workforce crisis.

“It may be time to ask: Is there a better model?” she said.

WARD OF THE STATE

Adults who need a high level of care, sometimes round-the-clock, are typically placed in community-based group homes. Others live in their own homes and receive a lower level of services. The services are contracted out to a variety of agencies scattered throughout the state. This is the system that was created out of deinstitutionalization, when large institutions like Pineland closed because they were providing substandard, and in some cases, inhumane care.

The system has long been a work in progress and in recent years has been plagued by long waiting lists for services, although the Mills administration included funding for an additional 167 people in its recent budget.

The state would not answer questions about Fisher’s services, and his guardian, Bourque, did not respond to emails or phone messages from a reporter. But probate court filings shed light on the man’s care.

Fisher was born into poverty in the late 1950s and lived in foster homes as a child in Biddeford. Because of an intellectual disability, he never learned to read or write, but he held many jobs over the years and developed a passion for art later in life.

He lived most of his adult life in the Biddeford, Saco or Old Orchard Beach. He often had roommates, according to his sister, Rachel White, who lives in Westbrook.

Art by Norman Fisher Photo courtesy of the Art Certificate Program of Biddeford

White was not close with her brother. They were separated as kids, White said, because their parents were too poor to care for them.

Fisher was receiving in-home services prior to the state’s petition for guardianship in 2014.

In 2015, after he was found living in a squalid apartment and consuming rotten food, a judge ruled him incapacitated and he became a ward of the state. The state becomes a guardian only as a last resort but said in a court petition that no one else had come forward. White said she never was contacted during the guardianship proceeding and doesn’t know whether she would have assumed the role of guardian.

According to annual reports filed with the probate court, Fisher needed help with daily hygiene and with taking insulin to treat his diabetes. But he was independent, too. For many years, he lived in downtown Biddeford and was well-known to many there.

Art by Norman Fisher Photo courtesy of the Art Certificate Program of Biddeford

Lianne Lewin-Grover met Fisher when he became involved with an initiative called the Art Certificate Program.

“He was an amazing guy and such an important part of the program,” she said. After Fisher’s death, the program held an art show in his honor and has named its gallery after him.

In a July 26, 2019, report to the probate court, Bourque indicated that Fisher was being evicted from his Biddeford apartment and would need another option. Fisher didn’t have a place to go immediately and ended up in a hospital, Meltzer said. The state has for many years been forced to house adults like Fisher in hospital beds when no other options are available. Some stay in hospitals for months. Some end up out of state.

One of the biggest contributing factors to a lack of services for this population, according to Hymanson, is the state’s workforce shortage. There aren’t enough people to fill critical jobs and when there are, would-be workers choose other professions because they can make more money. Dawson, with the providers’ association, said the Medicaid reimbursement rate for direct care workers supports a wage of just over $11 per hour.

“Consequently, qualified direct care workers are fleeing the sector for higher-paying positions in fast food establishments, retail and call centers, and other entry-level work requiring less training and experience,” she said.

When Fisher finally found a place to live on Humboldt Street in Portland through RCSS, that may well have been his only option.

WIDESPREAD DEFICIENCIES

Two years ago, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Inspector General released a damning 77-page report that found widespread deficiencies in Maine’s system for providing care to adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

At the time, then-Commissioner Mary Mayhew of the Maine DHHS downplayed the findings and insisted that things were better, even as advocates said otherwise. Among the issues cited were that providers were not doing enough to record deaths, injuries or other serious incidents and that the state wasn’t properly investigating the deaths of adults in the system.

That has changed, as evidenced by how the state handled Fisher’s death. According to Maine DHHS, the state immediately suspended new admissions to RCSS and launched a program audit that included a plan of correction from RCSS. The state decided that the agency didn’t do enough to make improvements and last week terminated the MaineCare contract that had been in place since RCSS was founded in 2013. DHHS also terminated RCSS’ separate state contract to provide emergency transitional housing services.

In addition to Fisher, the state investigated two other deaths of clients in RCSS care but determined that no action was warranted. Disability Rights Maine, the independent organization that advocates for clients under a contract with DHHS, also had longstanding complaints against RCSS, according to executive director Kim Moody.

Nagel, head of the Brunswick-based provider Independence Association, said it is widely known that there are agencies that don’t provide services the way everyone else does and he included RCSS in that group.

“But part of that is because they are serving some of the most challenging people, people no one else will take,” he said.

That seemed to be the case with Fisher. Meltzer, at Sanford-based Waban Projects, said Fisher had some behavioral challenges and his understanding was that other service agencies signaled they would no longer work with him. Meltzer said Fisher’s case manager was actively trying to find placement and worked closely with the hospital during his discharge. He said he didn’t know about the medication question, though, or about the guardian’s role.

Estabrook, the former advocate, had some sympathy for RCSS.

“It also seems like RCSS hardly knew this patient. That’s a problem,” he said.

Estabrook said if Fisher was hospitalized, his team should have had a plan in place for when he was released. That team would have certainly included Fisher’s guardian.

RCSS has alleged that Fisher had a right to refuse medical care, but Estabrook said he believed the guardian would be the one to give consent because Fisher was incapacitated. However, he also said there are provisions to forcibly medicate someone if his or her life is at stake. Farwell said the state believes providers are required to act without waiting for permission of a guardian.

All of the advocates and providers who spoke said the state’s action was not unprecedented but certainly rare.

“In the past, the state has known about bad providers but has turned a selective blind eye because there were no other options,” Nagel said. “I applaud the administration for taking this step. It seems like they are trying to clean things up.”

Attention now turns to the 65 clients who are still under RCSS care. The state is working with other providers to find new homes for them and has said it’s confident that will happen. But it’s the same system that couldn’t find a home for Norman Fisher.

That’s why Hymanson said the state needs to ramp up conversations about bigger changes. She said it’s clear to her that small, one- and two-bedroom group homes with little oversight aren’t the answer. Large-scale institutions weren’t either. What about something in the middle, she offered.

Rachel White, Fisher’s sister, said even though they hadn’t talked much, she was saddened by how his life ended. She doesn’t even know where his remains are.

Kevin Kilcline at Advantage Funeral and Cremation Services said Fisher was cremated there. His remains were picked up in September. The authorization for release was signed by Bourque, the state guardian.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story